This story is about the paradox of “progress,” philosophy, and … soap.

Here is a family story. My great grandmother was a wise village woman. She was healthy well into her old age, and when the family eventually moved to the city, she kept her village habits. She walked everywhere on foot—even very far—and never took the bus.

Before the revolution, when she was still a young girl, the women in the village did family laundry in the river all year round. For “laundry detergent,” they boiled wood ashes and used it as “soap.”

When I first had the story of washing the clothes with boiled wood ashes in the river, I reacted to it like a modern person (“oh how lucky we are today that we have proper soap and don’t have to resort to such primitive ways”). And then I was stripped of my initial arrogance when I learned that some of my favorite soaps of today are made with boiled plant ashes, and that boiled ashes clean grease and kill unseemly bugs really well—without poisoning us. And, unlike in the “primitive” days, I can only pray that the ashes used in my favorite soaps don’t contain any microbiome-nuking pesticides, etc. Yeah, “progress” offers great comforts and an ability to spend time on the things that the conveyor masters had trained us to love—but a bit of a joke is on us.

How did soap came about?

History of soap

We know from cuneiform tablets that 5000 years ago the Sumerians were boiling ashes together with animal and vegetable fats to make a slurry that they used for cleaning. Similar recipes for soap made from alkaline salts mixed with oils have been found on Egyptian papyri dating as far back as the New Kingdom (circa 1500 B.C.).

Although there is no proof of it, an old Roman wives’ tale holds that women who lived near Mount Sapo discovered soap when rain washed a combination of wood ashes and animal fat into the clay soil by the Tiber River where they were doing laundry. The famous Roman natural historian, Pliny, disputed this claim and credited soap’s invention to the Gallic and Germanic tribes the Romans encountered during their conquests. In any event, what is more definitively known is that Romans were using soap in their baths by 200 A.D.

After Rome fell to the barbarians [sic] in the late fourth century A.D., soap use dropped precipitously. One of the few institutions remaining in the west, the Roman Catholic Church, discouraged bathing because it was seen as too like the hedonistic and pagan ways of the old empire. Many people followed this advice, and the general lack of hygiene and sanitation is now thought to be a primary contributor to the spread of the Black Death (1348-1350), among other diseases.

Nonetheless, some people were bathing with soap even during the Middle Ages. For example, the Crusaders developed a taste for soap and brought the recipe to make Aleppo soap from olive oil back to Europe from the Middle East; as a result, soap making flourished in Spain during the 11th and 12th centuries, where Spanish Muslims made Castile soap. Likewise, soap made from wood ash was produced in some of the larger towns in England during the 13th century, and by the 1400s, French mysophobes were making Marseille soap by mixing seawater, ash and olive oil.

Prior to the 18th century, however, soap use still was not wide spread. Not only was it too expensive for everyone but the wealthy, but most soap had an unpleasant aroma as well…

Many claim that the real turning point in making soap ubiquitous came during the mid-19th century. Early in the Crimean War (1854-1857), fought by the British in what is today the Ukraine, most of the deaths the British suffered came from disease rather than battle wounds. After Florence Nightingale brought hygiene into British field hospitals in late 1854, however, British deaths decreased. This lesson was not lost on Americans who, during their Civil War (1861-1865), instituted hygienic reforms among soldiers. Having become accustomed to regular soap use, soldiers returning from battle brought their new, clean habits home.

The rise in soap use also coincided with the development of mass marketing. One of the early giants in the commercial manufacture of soap, Proctor & Gamble (P&G), realized the importance of creating a brand, having an appealing package and then advertising the product on a mass scale. According to reports, P&G spent more than $400,000 a year on advertising in the early 1900s, an amount equivalent to $10,000,000 today. (This advertising was so ubiquitous that daytime drama serials began being called “Soap Operas”.) That money was well spent, and by 1930 the demand for P&G soap was so great, it was being made in boilers that were three stories tall.

This plot omits the fact that soap from ashes and oils has been used in Africa since time immemorial, so it is very likely that first soap first came to my home continent of Eurasia from Africa —and then spread around.

In the Americas, the locals used various “soapy” plants to wash their bodies and clothes and—unlike the Europeans who at the time weren’t into bathing, practiced superb hygiene (and complained about the way the unwashed Europeans smelled). Speaking of bathing, even though home-made soap allegedly had some use among the settlers, it was not until the late 19th century that Americans of European descent starting warming up to the idea of regular bathing.

Most Americans in the first part of the nineteenth century didn’t bathe. There was little indoor plumbing, and besides, everyone knew that submerging yourself in water was a recipe for weakness and ill health. But historian Jacqueline S. Wilkie explains how things began to change toward the middle of the century.

First in Britain, and then in America, concerns about cholera and other disease borne by contaminated water drove cities to expand water and sewage facilities. With plenty of water easily available indoors, some of the nation’s wealthiest people began using bathtubs. The first fixed tub installed in a private home may have been installed in 1842 in Cincinnati.

At first, bathtubs were expensive, Wilke writes. The earliest ones were made of painted sheet metal that had to be carefully shaped from a single sheet, or crafted from expensive porcelain. Tubs made of copper or zinc-lined wood were a bit cheaper, but also more prone to leak.

Still, the idea that a bathtub was a useful facility trickled down to the middle class through books and magazines about domestic life. Ideas about bathing evolved as the technology improved. Wilke writes that doctors, social reformers, and domestic advice-givers provided various rationales for bathing as a healthy practice. Some leaned on old-fashioned medical theories involving the balancing of humors and the elimination of bile through the skin. Others suggested a tepid bath for refreshment and revitalization. By the 1860s, expert opinion was nearly unanimous that the best kind of bath was a brief plunge in cold water to relieve congestion of the brain and fight anything from cholera to whooping cough. For the most part, hot baths were a no-no, as was actually relaxing and enjoying the water.

“However pleasant a long-continued bath may be in hot weather, yet it is by no means to be recommended,” British domestic engineer J.H. Walsh warned in 1857. In fact, parents should yank kids out of their baths, lets they “dabble too long in the water and thus do absolute injury to themselves by carrying to excess what is otherwise a most valuable adjunct to health.”

The focus of bathing was not to remove dirt, and few experts suggested the use of soap. One physician suggested soap only for excessively dirty bodies, since it removed necessary oils from the skin.

By the way, there is also a school of thought according to which it is better to bathe more rarely so as to preserve the skin microbiome. There might be some truth to it—and I bet that in terms of preserving the microbiome, there is a significant difference between bathing in a river 300 years ago with the help of natural soap or medicinal plants—and bathing in the rusty, chlorinated water of today using industrial soaps—but all is good in balance, and, in a modern city like New York, regular bathing still does not seem like a bad idea at all. :)

Here are a few videos about soap, they are simple but I learned a few things.

New or forgotten old? A paradox of progress that is driven by the quest to conquer and subdue

Here is the paradox: in the olden “primitive” days, our ancestors in the so called “pagan” (“rural”) cultures generally structured their lives around the real reality of living on Earth. They made it a point to live in a way that makes us happy, healthy, and satisfied in this world. They nourished relationships and joy, respected the spirit with aliveness, practiced good hygiene that worked for people in nature, and had a very precise hands-on science, including a great knowledge of medicinal plants and herbs.

The separation from joy and natural health happened in phases. First, the “civilization” came wearing a theological coat—and wiped a lot of the traditional joy and knowledge out. Deprived and deflated, the people got unhappier and sicker.

Then “civilization” came wearing an industrial coat. It came with “modern” hygiene but it also brought large-scale poisoning of nature and of the human microbiome. And at that time, the people got better protection from what had been ailing them after the first ‘bout of rape, but they immediately got sicker in more surreptitious, lingering ways, and today’s “healthy” people often resemble well-oiled robots: a pumped-up rosy body and dim eyes.

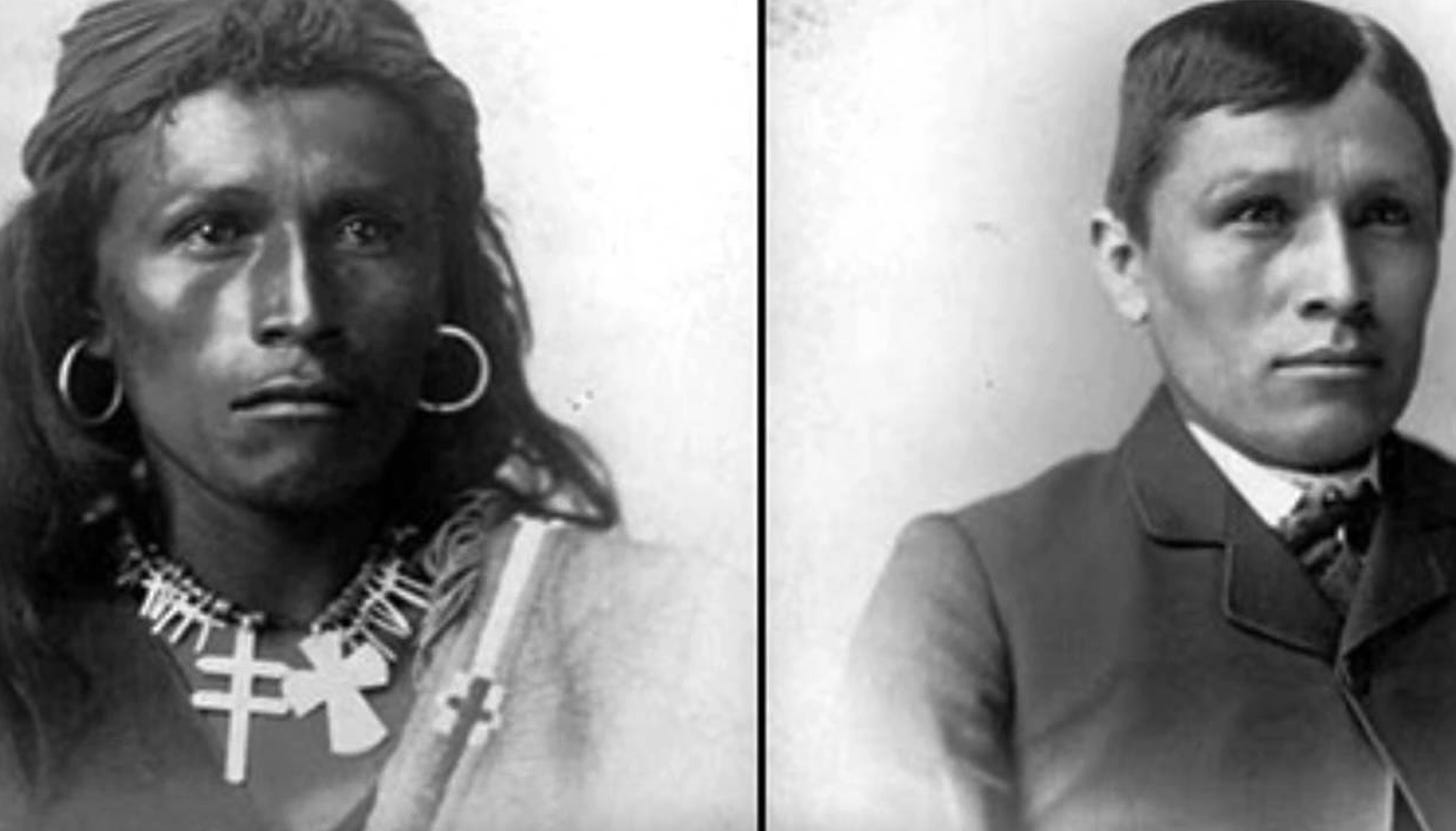

The photo below is often shared as an illustration of the campaign by the great resetters of the day to “kill the Indian, steal the tribal land, save the man, and by save we mean turning him into a zombie cog in our, great resetters’ machine.”

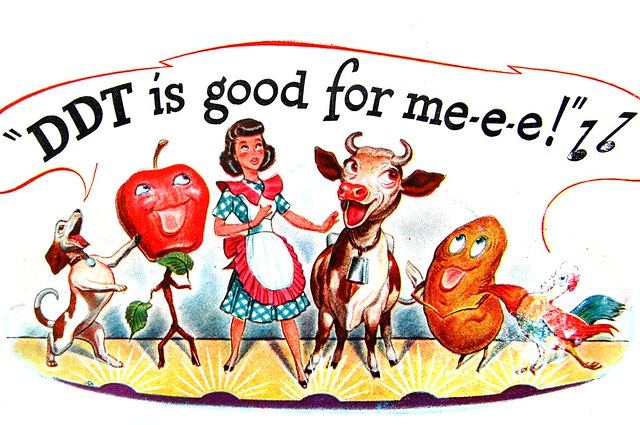

And here is the famous advertisement for safe and effective DDT.

Soap missionaries

Soap missionaries (the term that I just made up) are the learned men and woman who go to “developing” counties to teach the locals to use modern soap. An example of a “soap missionary” was Val Curtis, whom I wrote about in 2022. (The article is on behavioral immunity, “disgustology,” social engineering, and the use of fear of contagion to “inspire” people to comply.)

Val Curtis was a British scientist, a passionate hygiene proponent and the Director of the Environmental Health Group at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine… In 2020, continuing her public health mission, as a member of the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behaviours and a contributor to SAGE, she advised the UK government on how to “encourage people to adhere to recommendations… She passed away in October 2020.

When she lived in Africa, she worked with passion on teaching the African villagers to use soap, which is a tad ironic given that Africans have been using soap much longer than Europeans. Human relations sure are complex, and history is full of twists!

Making a full circle: gettin’ weak and consequently gettin’ plagued

Yes, history is full of ironic twists. Today, due to the poisoning of everything on an industrial scale, an overuse of toxic antimicrobial cleaners, and biologically contaminated vaccines, the supposedly clean modern people are dealing with antimicrobial resistance—which the WEF loves—and a whole large crew of underdiagnosed unsexy bugs (that lead to mysterious symptoms, for which the learned men come up with fancy fictitious syndrome names, and the gullible doctors prescribe more toxic drugs, etc.)

What will happen? Will we believe the next ‘bout of the great resetters deadly fairy tales (see this paper on AMR and the WHO”s “pandemic treaty”)—or will we cry to the skies and remember how to live in a way that makes us, human beings ,happy, healthy and satisfied on this Earth? What will it take for us to remember how to snap out of robothood and come alive?

A note to readers: If you are in the position to do so, I very much encourage you to become a paid subscriber or donate. I love you in any case, but it helps A LOT, and I am in a dire need to get more donations and paid subscribers while keeping my posts free. Thank you from my heart for your support!

My entire street smells like dryer sheets...has anyone else noticed how most people smell like Tide/detergent nowadays?

Wood ash is incredible on so many levels. Thank you for paying homage to our ancestral wisdom Tessa!

Check out soapnuts. Non-toxic and no smell. They work great. I’ve been using them for years. Sapindus Mukorossi